Classical European Illusionism Is Only a Late Development in an Inherently Abstract Art

Viking Longship / Creative Eatables

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Brewminate Editor-in-Master

The artistic and architectural stylistic, methodological and technological aspects of earth cultures have, with rare exception, displayed bilaterally direct and indirect influence while leaving their unique historical fingerprint. Pyramids and ziggurats withal stand up equally testaments of Egyptian and Sumerian technology in addition to the hieroglyphic and cuneiform scripts and consequential décor. Ornate amphorae, kouros and koroi sculptures, formal canons through conspicuously defined periods, the idealism of the Acropolis and the realism of Hellenistic works are reminders of the age of the stunning progress of the Greeks who borrowed much from Mycenaean and Minoan societies earlier them and were themselves copied at length in the piece of work of the Roman Empire. The artistic styles and especially architectural technologies of the Romans laid the groundwork for the Romanesque and Gothic movements that would after explode beyond Western Europe and leave in their wake Merovingian, Carolingian, Celtic and other style incarnations. Though Scandinavian and particularly Dutch cultures would also produce new styles and techniques, the Viking Age itself stands out in the history of culturally unique artistic advances in the sense that they more often than not did non create fine art for fine art's sake. They were known for their mastery of piece of work with metal, wood, and horn or bone – materials that were vital to their culture. Viking art was adult in a utilitarian textile culture with décor and ornamentation primarily secondary to functionality and meaning, requiring a fine semantic line to be walked between art and craft (a line that exists precisely because of the dual nature of many of their material objects), which is attested to by their work with and mastery of these materials. A bowl, for example, was created for its practical utilise as a bowl, and the symbols carved into it were not aesthetically inspired but held some pregnant meaning. Viking art evolved through aesthetically dualistic stages of style, and in combination with that of especially the Anglo-Saxons,[1] left its fingerprint in morphing Celtic art motifs and early Romanesque architectural designs.

Iconography in the earliest years of the Viking Age was replete with animate being motifs. Recognized every bit the earliest "style" of Viking fine art – dated C.780-850 CE – was the Broa style, also called the Oseberg style based upon artifacts discovered in a Viking send grave nigh Oseberg in Kingdom of norway. The imagery, called the "gripping beast" motif, was replete with many curves, bends and turns, the subject area creature often "gripping" the borders of the piece on which it appears. Undoubtedly the most recognized representation of this mode is the mail discovered on the Oseberg transport burial. This highly energetic design would eventually come to be known as dynamic animal interlace style.[2]

Oseberg Mound Excavation / sites.google.com

The Vikings worked heavily with metal, bone, ivory and wood, and all of their designs were incorporated onto these materials that were used for every day purposes. The utility of the piece of work – its function – was master and the motif secondary to it, though certainly containing important symbology. This would besides affect the Anglo-Saxon globe every bit similar materials have been discovered amidst their settlements as well containing similar motifs.

Animal-Head Post from Oseberg Mound Excavation / Wikimedia Eatables

Viking ships were unremarkably decorated with a posts representative of a serpent or dragon. Great attention was paid to such details on their ships as they were a seafaring people, not but evident in their ships and sailing ability simply also in their stories and mythology. The posts were not just added to ships for the sake of appeal, only for a people steeped in superstition and conventionalities to ward off monsters of the body of water, leading enemies and others to telephone call them "dragonships" – "drakuschiffen."[3] Stores of such monsters were not just limited to the sea in Viking life. The lindorm was a particular land-based monster of Norse sagas, typically described as a big dragon or vicious serpent, bringing aground the superstitions of sea travel. In Ragnar'south Saga Lobbrokar, an old man speaks of vanquishing such a monster he referred to as "the globe fish."[4] Over time, with increased Viking settlement and colonization of conquered areas, the lindorm was separated from sea serpents and dragons in stories every bit peasants living on state came to fearfulness the same devouring as their seafaring kinsmen, the two being described and depicted differently in art.[five] So painstakingly constructed and effective were the Viking longships that they were the most efficient and feared vessels on the open up seas in Viking Historic period Europe.[six] History is total of examples of culture and ideas existence exchanged between different peoples on merchandise routes, and the same concept would have been no unlike with artistic and architectural styles being transferred through other means such as conquests and raids.

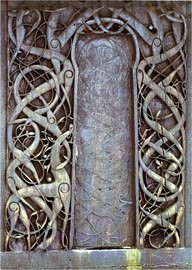

The influence of the dynamic Oseberg style was later evident in Christianized Scandinavia, in combination with what would exist final Urnes mode. Setting bated for the moment that particular fashion's contributions, the Oseberg influence on the Urnes Stave Church building in Urnes, Norway, copies the ship'due south post. However, the Oseberg fashion influenced only portions of the door, the residuum existence influenced by the later Urnes mode.

Urnes Stave Church Portal / Wikimedia Commons

Immediately noticeable on the church portal is the serpent blueprint of Viking mythological origin, influenced by transport prow serpents and dragons. The blueprint, as the animals symbolized within them, instilled in the viewer a sense of loftier free energy and ferocity.[7] Just as each style would independently too every bit in combination influence afterwards Scandinavian, Anglo-Saxon and European Romanesque art and architecture, each influenced the ane that followed in natural progression.

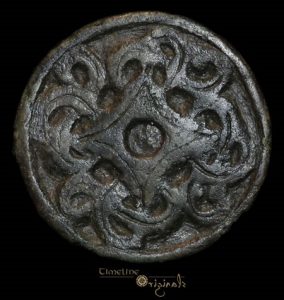

The waning of the Broa/Oseberg fashion saw the rise, from C.840-970 CE, of the Borre Style. The dating of each way is so specific given the rapidity with which each style arose and spread across the Norse globe due to the equal speed with which different regions were able to communicate with each other.[viii] This manner was also named for a transport burial not far from the Oseberg discovery, further solidifying the importance of the sea to the Viking and its condition as an intrinsic part of their culture. Had it not been for the sea, at that place arguably may never have been a Viking Age. Though viewed by some scholars equally less impressive than its immediate predecessor,[nine] the Borre style contributed equally all others to a style that evolved as needs evolved. Taking its name from statuary harness mounts employed in Borre, Norway, this mode was primarily used in blueprint decoration of much smaller items. It was typically used to embellish jewelry, trinkets and other items. Had these items been inherently decorative, then coupled with the motif this would take been exemplary of creative intent. Simply jewelry, for instance, though often elaborately decorated, served a purpose for the Vikings. Vikings were raiders, and collection of cloth wealth was a driving strength. In a culture containing master metal and wood craftsmen, a raider's gains would oftentimes be converted into jewelry and worn by family members to reduce the demand for storage and prevent theft. Jewelry was likewise used in trade every bit well as to display wealth and condition and to seal friendships and alliances.[10]

Viking 'Borre Mode' Disc Brooch / Jonah Lobe, Pinterest

Linde Church Portal / Thyra Blog

The primary difference betwixt the Borre and Oseberg styles rests in the heavy the states of a ribbon plait motif in Borre artifacts. The pattern is a symmetrical interlace blueprint that was fairly uniform across all mediums. Instead of the ferocious serpents and dragons of Oseberg, this style featured a full general brute mask at the circles where the ribbons joined. The free energy of the Vikings connected to be symbolized even with the changing iconography. As with the Oseberg style, the Borre fashion besides influenced early Romanesque architecture. The Linde Church building in Linde kirke, for example, contains early on Viking styles such every bit the Borre still being added every bit late as mid-fourteenth century.

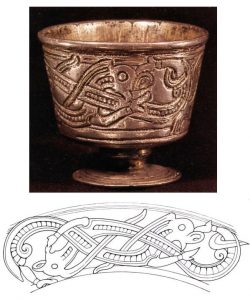

Arising at approximately the same time as the Borre style and running near concurrent to it, from approximately 880 to 1000 CE, was the Jellinge style. Immediately following that of the Jellinge was the Mammen mode from C.950-1030 CE. The two were separated by only minor differences and are frequently referenced together. Again, this was discovered on relics in a purple burial mound (this on land compared to the previous styles from ship burials) in Jellinge, Denmark, hence its subsequent name. While the sinuous and dynamic nature of the patterns continued, this motif incorporated animals absent the "gripping creature" motif axiomatic in the earlier styles. The animals were typically depicted in profile with the "ribbons" largely consisting of the animal bodies every bit opposed to seemingly abstract patterns.

Intertwining Dragon Motif on Jellinge Cup / Wikimedia Commons

Jellinge Style Relic / Thyra Blog

Cups, chairs, and other relics containing this way again incorporated the design every bit a secondary feature to the utility of the item being embellished and for the significance of the symbolism. Even on land-based artifacts such as these, the influence of the importance of the sea in Viking culture remains. That which gave rise to their civilization was kept in visual proximity, thus always in mind. The Jellinge mode retained the influence of the preceding Borre motif in a opposite mode – whereas the Borre mode largely miniaturized the Broa/Oseberg designs, the Jellinge introduction one time again saw the enlargement of the designs. The previous ii styles did not but fall by the wayside with the introduction of these successors. Over again, the utile aspect of the culture was the determining gene in which to use. The Oseberg/Broa motif was well-suited for the early longships, the Borre for the smaller jewelry and trinkets, and the Jellinge for the more than mid-sized items such equally the burial mound cup. The materials were non adjusted to adapt the design, but the blueprint adjusted to adjust the item in question.

The Jellinge style would become highly popular and its influence would go along in the design of artifacts in later on Normandy and England post-obit the reign of Cnut.[11] The patterns of animal motifs employed in Jellinge mode artifacts, dissimilar the seemingly disorganized patterns of earlier styles, frequently incorporated symmetrical designs. This utilise of symmetry was mayhap an aspect of pure aestheticism coupled with the utile nature of Viking art.[12]

Jellinge Vertical Symmetry (left) and Jellinge Horizontal Symmetry (right) / Wikimedia Commons

The preceding styles were shown to have influenced later on Romanesque compages, merely the Jellinge motif was immediately seen in much larger sculptures and monuments.

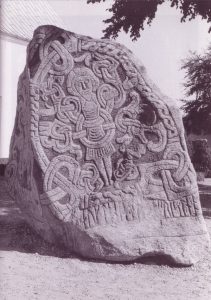

Jelling Monument, Crucifixion / Arild Hauges Runer

Christianizing influences saw the rise of monuments containing familiar Viking designs then attached to the symbology of the Church. After Harald'south conversion to Christianity in the 960s, he had a monument erected in Jellinge itself depicting the crucifixion of Christ, and the Jellinge pattern and pattern was incorporated onto that monument. Earlier styles were used to describe Infidel beliefs and mythology, and the Jellinge arose as the first to incorporate Christian iconography.[13] The Mammen way, surviving the Jellinge for thirty years, brought these diverse motifs to much larger monuments, and this trend would literally explode under the final styles.

The Ringerike motif, dated between 980 and 1070 CE, followed the Jellinge and Mammen styles. The Ringerike style was an extension of Mammen iconography and greatly expanded its use. Vikings survived off the country in a largely pastoral lifestyle given the express agrarian opportunities provided by the land. But as the Egyptians had long before them used the papyrus plant for scrolls with many stylistic designs, and so too did the Vikings incorporate into their items of everyday and cultural use those aspects of the land closest to them. Ringerike was simply a Norwegian commune containing the nigh typical examples of the type of flora and fauna native to Norway.[14] The Vikings had a history of runic monuments commemorating lives and events, and the Ringerike style would be used at length for this purpose, existence coupled with what had historically been monuments in which runic symbols were carved but that contained no decorative embellishment. The influence would spread to England every bit had other styles. London finally succumbed to Viking raids in 1016, beingness ruled after that point by King Cnut and his sons Harald and Harthacnut through 1042.[15]

Ringerike-Mode Grave Slab, St. Paul's Cathedral Churchyard / Wikimedia Commons

Ringerike iconography changed somewhat from previous styles in two primary ways. First, the dynamic creature interlace design was much less pronounced and seemed to be used to compliment the imagery rather than as a direct role of it. Second, a new creature was introduced in the imagery along with the serpent, that being the king of beasts. Syncretic cultural combinations inevitably required that this long-seafaring people comprise imagery in conquested areas with which local people could connect more than easily. The lion, equally had the dragon at sea, represented a bully deal of strength and was a common symbolic prototype in the British Isles prior to Viking incursions. A grave slab in the churchyard of St. Paul's Cathedral diameter testament to the combination of the two cultures. Wooden panels in Republic of iceland have been compared to Byzantine influence also, indicating that influence from far eastern Europe found its way to the Scandinavian earth every bit well.[xvi] At that place is even conjecture that the runic script used on numerous Viking monuments was itself developed in Romanized provincial regions of Northern France and afterward adopted past the Norse people equally they adapted it with their own script for their own use.[17] Regardless of the influence for the Viking cosmos of runic inscriptions and later design adaptations within their own culture, it was evident that the way was afterwards adopted by regions falling under Viking control.

The last recognized Viking art style was the Urnes style, developed betwixt 1040 and 1150. Whereas the Oseberg/Broa, Borre, Jellinge, Mammen, and Ringerike motifs took their names (respectively) from ship and mound burials, jewelry and small trinkets, larger monuments, and runic stones, the Urnes design was named after the last leap of Viking artistic style in architectural design. It specifically references the motif of the carved wooden doors of the Urnes Stave Church, built around 1130, in Urnes, Norway. Portions of the portal comprise influence of the commencement Oseberg/Broa way in the Heathen behavior continuing in the civilization even in the face of and actually forth with Christianization, just the serpents and other animals begin to "bite" themselves in this design and the curves are not every bit asymmetrically convoluted equally in Oseberg.

Urnes Stave Church Wooden Portal (left) and Pickmoss Medieval Timber House (right) / Wikimedia Eatables

Every bit medieval architectural styles connected to evolve in the British Isles and elsewhere, the influence of the Urnes style is evident in combination with regional motifs that began to take on more formal representations, completely Christianized just with the same dynamic interlace. Structures such as the Pickmoss Medieval Timber Business firm in Oxford depict this combined influence. The Urnes fashion was the culmination of Viking artistic design, each style developing not in and of itself every bit an aesthetic cosmos but instead total of iconography and symbolism that served a spiritual purpose in combination with the applied purpose of the particular upon which the fashion appeared.

The Urnes mode grew through four different stages, and exam of those stages provides an overview of the final influence of Viking designs on Romanesque architecture in Northern Europe. The early Urnes style, dated from C.1050 to the early part of the twelfth century, presented the overall combat motif of the style in image and text, commemorating the conquest of other lands by noted Viking leaders.

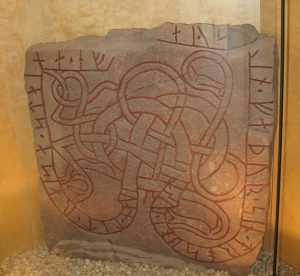

Runestone U-343, 18thursday century drawing (left) and Runestone U-344, Orkestra, Sweden (correct) / Wikimedia Eatables

The style was named after two rune rock monuments, referenced as U343 and U344, discovered in a churchyard in Yttergärde, Sweden, both attributed to the runemaster Åsmund Kåresson of Uppland. The stones were later moved to the church of Orkestra, Sweden. The stones celebrate the capture of iii danegelds in England by Ulf of Borresta, hence establishing the style every bit one commemorating such events. Again, the design was non chosen for its aesthetic appearance but instead how information technology contributed to the object and the message. This motif would proceed through the mid-Urnes manner, which was uniquely applied to coinage. Equally the style approached its latter stages in the early role of the twelfth century, the animal designs underwent a key change nether the manus of runemaster Öpir of Uppland, Sweden. The animals he depicted were very thin in patterns much more circular than before motifs, clearly depicted on the Jarlabanke Runestones.[18]

Runestone U-216, Church of Vallentuna / Wikimedia Commons

These runestones, a group of twenty in Uppland containing the Younger Futhark rune script, were believed to have been deputed by Jarlabanke, a chieftain of what was called a "hundred" ("hundreds" being subdivided regions to disperse rule in a autonomous manner), hence their proper name. The circular pattern with sparse animals could exist seen in the U-216 runestone discovered at the Church of Vallentuna, one of the Jarlabanke stones.

The Urnes designs on the stones stopped with them, but their influence continued into what became the Urnes-Romanesque architectural style. This final phase of Viking artistic style saw the ultimate fusion of Viking iconography and design and the local Northern European Romanesque styles that were start to rise, the syncretism that resulted as the Viking people continued to migrate and eventually became a "new" people in Normandy, their days of seafaring, raiding, and pillaging at an end. Traditionally dated to between 1100 and 1175, this Urnes-Romanesque style was a testament to their indelible influence on European artistic culture, and the European influences continued to infiltrate Scandinavia as well with ongoing Christianization. This influence in which local Scandinavian traditions were permanently influence was evident in the Lisbjerg altar frontal in a church near Aarhus.

Lisbjerg Altar Frontal, Denmark / Wikimedia Commons

The altar'due south design is busy and energetic, as was the dynamic animal pattern of the styles that built up to it, but it became much more organized and settled into a more formal iconography. The Viking styles establish their influence in such doors, portals, altarpieces, and various smaller portions of the larger Romanesque structures that would rise in cities across Europe. A church entire of itself could not be seen from a distance and immediately identified as one influenced by Viking iconography. But closer inspection of these areas of the structures would have held familiar motifs and patterns to especially Viking immigrants and their descendants, and the designs would keep to influence and meld with other cultures – especially that of the Anglo-Saxons, who themselves had their own unique dynamic animal interlace style that had earlier influenced the beginning style stages of Viking art, an influence that was and so returned to information technology for connected growth and development. The utilise of the Scandinavian motifs in Northern European Romanesque and Celtic design was seen in structures such as Cormac's Chapel in Dublin after the Viking historic period had passed. The larger structure adhered to the typical Romanesque canons of the twenty-four hours, but Viking iconographic and design influence was axiomatic in sure details and even in a carved sarcophagus.

Cormac'south Cathedral (left) and Sarcophagus in Cormac'south Chapel (correct) / Wikimedia Commons

A combination of practically each manner of Viking artistic history plays a role in the design of the sarcophagus, and its use and placement in a Romanesque church spoke to the syncretic relationship between European compages and Viking art.

The Viking Age was equivalent to the blink of an eye in historical terms, and historians have ofttimes dismissed its influence upon the ongoing and developing creative and architectural traditions of continental Europe every bit well as the British Isles. Their cultural contributions have frequently been disregarded in word, which has all too oftentimes focused too heavily on the raiding and trading Viking tradition. To exist sure, that was certainly an integral part of what it meant to be a Viking and how they rose to create a cursory empire of sorts in their part of the world. But to ignore or minimize the importance of their artistic iconography would exist a disservice to their history. Fine art for art's sake was non a function of the Viking tradition. Symbols were incorporated into everyday objects, gravestones, runestones, ships and other necessities of life to gain protection, commemorate a person or event, or to tell a story in imagery equally the skaldic poets did in operation. Because of that applied apply of each style and motif, outside influence is practically not-existent in Viking fine art in terms of design. However, that external influence that does exist was heavily related to the Christianization of Scandinavia – the purpose of the symbols did not change, but the symbols themselves did, such as the crucifixion scene displayed on the Jellinge monument. Every bit Vikings diffused onto the European continent into Normandy and from at that place to the British Isles, their styles adapted to a changing culture and the combination of the ii is axiomatic in portions of Romanesque churches that literally exploded across Europe in structure prior to the Gothic era. Many of those churches still stand and hold inside them evidence of a people who left a permanent fingerprint on the earth. Regardless of what they eventually came to be called, what they left would encounter to it that their Viking heritage would non be forgotten.

[one] Gary Waidson, "The Real Celtic Art," < http://world wide web.lore-and-saga.co.uk/html/celtic_art.html>, June 10, 2008. "When Saxon and Viking art met, the effect was a striking combination of the best of both worlds."

[2] Ervan G. Garrison, History of Engineering and Engineering: Artful Methods (Danvers, MA: CRC Press, 1998), 111.

[3] Garrison, History of Engineering science and Technology, 112.

[four] A, Ragnar's Saga, Chris Van Dyke, trans. (Denver: University of Denver Cascadian Publishing, 2003), thirteen.

[5] Richard Svensson, "Viking Serpents: The Mystery Dragons of Sweden – from Norse Sagas to Modern Sightings," Fortean Times, July 2010, <http://www.forteantimes.com/features/manufactures/3880/viking_serpents.html>.

[half-dozen] Peter Sawyer, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 182.

[7] George Zarnecki, "Germanic Animal Motifs in Romanesque Sculpture," Artibus et Historiae (11:22), 189.

[8] William R. Short, Icelanders in the Viking Age: The People of the Sagas (London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2010), 175.

[9] David M. Wilson and Ole Klindt-Jensen, Viking Art (New York: Cornell Academy Printing, 1966), 87.

[10] Bonnie Smith, et al. Crossroads and Cultures, Volume I: To 1450, A History of the World's Peoples (New York: Bedford St. Martin's, 2012), 300.

[11] Due south.H. Fuglesang, "Swedish Runestones of the Eleventh Century: Ornament and Dating," In Runic Inscriptions as Sources of Interdisciplinary Research, K. Düwel, ed. (Sweden: Göttingen, 1998), 207.

[12] Deborah Kahn, "Norman World Art," History Today 36:3 (March 1986), 2.

[thirteen] A.G. Smith, Viking Designs (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1999), 52.

[14] Winroth, "Viking Sources in Translation."

[xv] T.D. Kendrick, Late Saxon and Viking Art (London: Methuen & Co., 1949), 98.

[16] Gabor Thomas, "Vikings in the City: A Ringerike-Style Buckle and Other Artefacts from London," London Archaeologist 9:8 (2001), 228.

[17] Selma Jónsdóttir, An xithursday Century Byzantine Final Judgment in Iceland (Reykjavik: Almenna Bókafélagid, 1959), 92.

[18] Tineke Looijenga, Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions (Boston: Brill, 2003), 100-101.

Comments

Source: https://brewminate.com/viking-artistic-development-and-stylistic-influences-on-later-scandinavian-anglo-saxon-and-western-european-romanesque-art-and-architecture/

Post a Comment for "Classical European Illusionism Is Only a Late Development in an Inherently Abstract Art"